Evaluation exhaustive de la façon dont les connaissances a priori façonnent la perception visuelle

- Imprimer

- Partager

- Partager sur Facebook

- Partager sur X

- Partager sur LinkedIn

Equipe Vision et Emotion, Recherche

---------- ENGLISH BELOW----------

Les modèles actuels de la perception visuelle considèrent la perception comme un processus proactif, qui dépend non seulement des caractéristiques des entrées sensorielles mais aussi en grande partie des connaissances a priori et des attentes que nous avons à leur égard. Mais dans quelle mesure ce que nous savons influence-t-il ce que nous voyons ? Le projet EXPER vise à répondre à cette question en évaluant de façon exhaustive la façon dont nos connaissances a priori influencent la perception visuelle. Nous testerons l’hypothèse selon laquelle nos connaissances et attentes sur l’environnement affectent qualitativement la perception visuelle (comment nous voyons ou même ce que nous voyons), via une série d'expériences psychophysiques impliquant des jugements subjectifs sur l'apparence de stimuli visuels attendus ou inattendus (objets en contexte), en tenant compte de diverses contraintes visuelles (e.g., temps de traitement, bruit visuel). Nous examinerons également pour la première fois les corrélats cérébraux de ces effets, ainsi que leurs conséquences fonctionnelles pendant la visualisation de scènes visuelles, à l'aide d'enregistrements en EEG et en oculométrie. Ce projet aura d’importantes implications dans le contexte du débat théorique de longue date concernant l’influence de la cognition sur la perception. Il permettra également de mieux comprendre ce qui détermine la perception subjective de stimuli attendus ou inattendus et comment celle-ci peut être affectée par des signaux bruités ou un déficit sensoriel (en conduisant par une nuit brumeuse, notre perception sera-t-elle dominée par les voitures attendues ou par la présence inattendue d'un piéton sur la route ?). Ce projet vise également à fournir des paradigmes fiables pouvant être adaptés à l’étude de ces mécanismes dans d’autres modalités sensorielles, ainsi qu’à la façon dont ils peuvent dysfonctionner dans différents troubles psychiatriques ou développementaux.

Voir les publications dans le portail HAL-ANR

To what extent does what we know influence what we see? Our visual system is constantly exposed to abundant streams of information which can often be noisy or ambiguous due to signal constraints (e.g., dim light or foggy weather) or sensory loss (e.g., in aging or visual pathologies). To rapidly make sense of the visual environment and adequately react, we must rely on prior knowledge built upon regularities learnt from our past perceptual experiences. In this context, this research aims at characterizing how our prior knowledge and expectations about the visual environment shape its subjective visual perception.

Find out more about key findings (so far) of this project below.

Expectations based on our prior knowledge influence “how well we see”

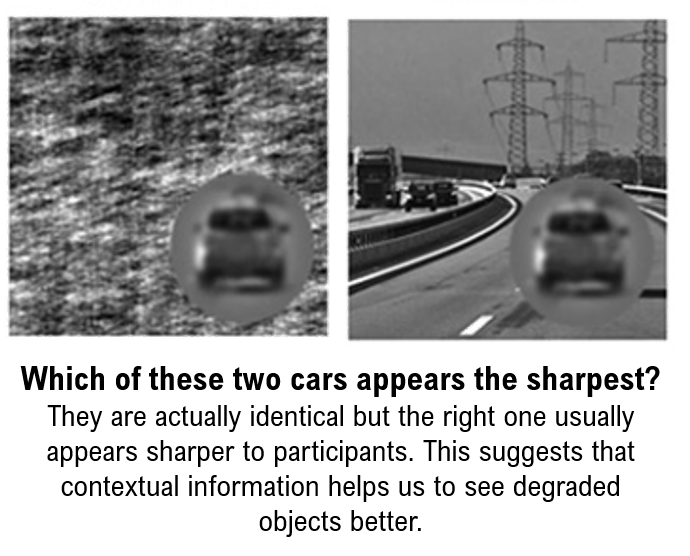

Imagine driving on a foggy day. The other cars in front of you cannot be seen well and just appear as blurry shapes. Yet, you have no difficulties in interpreting these blurry shapes as cars. This is because based on your prior experiences of driving, you know that in this context (a road), this is the most likely interpretation.

When visual objects are ambiguous, our prior knowledge about associations between objects and their context (what we call “contextual associations”) can thus influence how we interpret what we see. But can they also influence how well we see? For example, can our expectations about these blurry objects being cars make them subjectively appear sharper than they actually are?

In a series of experiments, we showed that blurred objects that can be expected based on their context (e.g., a car in a highway scene) are indeed subjectively perceived as sharper than the exact same blurred object that cannot (for example, a car in a meaningless context). Furthermore, we showed that expectations based on objects can reciprocally sharpen the perception of their context. A blurred scene context containing an intact context is perceived as sharper than the same context without a meaningful object. Finally, we showed that our prior knowledge and expectations not only influence subjective perception of objects and their contexts but also how we perceive entire scenes (for example, a blurred scene presented upright – which conforms to our prior experience of scenes – is perceives as sharper than the exact same scene presented upside-down).

These results indicate that the content of our perception can be strongly influenced by what we know and what we expect in our visual environment. But is it always the case? While relying on our expectations may help us see objects that are ambiguous better, it may be less useful when objects are clear and unambiguous. In the latter case, biasing our percepts toward what we expect could even be counterproductive as it could lead us to wrongly perceive objects that are unexpected (if a cow suddenly crosses the road on a sunny day, it would make no sense to perceive it as a car). In subsequent studies, we found that, fortunately, our visual system flexibly adapts to these constraints. When visual objects are ambiguous (blurred) we tend to rely on our expectations to make what we expect appear clearer and the effects of expectations on perception scale with the strength of our expectations. However, when visual objects are clear and unambiguous (or when we do not have strong expectations about them), their perception is dampened to the benefit of unexpected objects that may carry more relevant information to adapt our behavior.

What is the point of this research?

At a fundamental level, this research addresses a long-standing question in the field of cognitive psychology but also philosophy about the boundaries between perception and cognition. While it is well accepted that what we see influences what we know whether what we know reciprocally constrains what or how we see has been a matter of intense debate. Our findings therefore provide evidence in favor of this view by showing that objectively identical stimuli can be subjectively perceived as different depending on knowledge we have about them.

Addressing this question also has clinical implications. Visual sensory deficits are widely spread, especially in older adults who face pathologies such as age-related macular degeneration (loss of vision in the central visual field, predominantly used to process objects in details) or glaucoma (loss of vision in the peripheral visual field, predominantly used to process scene context). Understanding how our prior knowledge and expectations can influence how we see is therefore important to better understand how sensory loss can be somehow compensated by relying on these mechanisms.

What’s next? We are currently running studies to further characterize the extent to which what we know influences what we see and the neural correlates of these mechanisms. Stay tuned for updates!

Collaborators:

Carole Peyrin (LPNC)

Romain Grandchamp (LPNC)

Alexia Roux-Sibilon (Bourgogne University)

PhD Students:

Clara Carrez-Corral (2023-2026) - co-supervised with Carole Peyrin

Pauline Rossel (2020-2023) - co-supervised with Carole Peyrin

Main related publications:

Carrez-Corral, C., Peyrin, C., Rossel, P., Kauffmann, L. (2025). Effects of predictions robustness and object-based predictions on subjective visual perception. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13414-025-03150-2

Rossel, P., Peyrin, C., Kauffmann, L. (2023). Subjective Perception of Objects Depends on the Interaction Between the Validity of Context-Based Expectations and Signal Reliability. Vision Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2023.108191

Rossel., P., Peyrin, C., Roux-Sibilon, A., Kauffmann, L. (2022). It Makes Sense, so I See it Better ! Contextual Information About the Visual Environment Increases its Perceived Sharpness. Journal of Experimental Psychology : Human Perception and Performance. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xhp0000993

Coordinateur du projet

48 mois à partir de janvier 2023

- Imprimer

- Partager

- Partager sur Facebook

- Partager sur X

- Partager sur LinkedIn